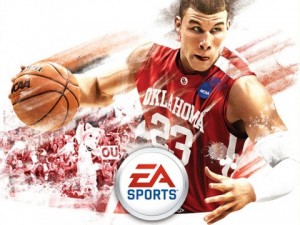

This week, as trial begins in federal court regarding O’Bannon v. NCAA, the fate of the NCAA’s current business model comes into question. This case, brought by former UCLA basketball star, Ed O’Bannon, challenges the NCAA’s practice of generating revenue by using a player’s likeness without compensation to the player.

This week, as trial begins in federal court regarding O’Bannon v. NCAA, the fate of the NCAA’s current business model comes into question. This case, brought by former UCLA basketball star, Ed O’Bannon, challenges the NCAA’s practice of generating revenue by using a player’s likeness without compensation to the player.

Really, it’s about fairness.

Meanwhile on another front, the NCAA will attempt to roll back a decision by the National Labor Relations Board in Chicago that allows the Northwestern University football team to form a union. The union came about when the student athletes requested their health insurance be extended beyond their scholarships.

Really, it’s about fairness.

Up on Capitol Hill, the House of Representatives will consider H.R. 2903, the “National Collegiate Athletics Accountability Act.” The legislation, introduced by Representative Charles Dent (R-Pa), seeks to eliminate the NCAA’s ban on paying student athletes.

Really, it’s about fairness.

Obviously, this is a critical time for the NCAA and how it does business. Unless the NCAA goes undefeated on these matters (and others) it’s safe to assume that 2014 will lead to a major tipping point for the NCAA business model. The NCAA is fighting for the status quo and seems to be holding on to as much ground as it can without compromising on any meaningful points.

The NCAA’s public response in each of these instances is consistent. Specifically, the NCAA claims to be the protector of the student-athletes and the importance of education – not money.

In the O’Bannon case the NCAA said, “the NCAA values and prioritizes all of its student-athletes regardless of whether their sport brings in revenue… but efforts to twist legitimate concerns about the current system into a rationale for paying student-athletes would do far more harm than good and would severely diminish the opportunities for academic and athletic achievement student-athletes benefit from today.”

In response to the NLRB decision allowing the Northwestern football team to unionize, the NCAA said, “This union-backed attempt to turn student-athletes into employees undermines the purpose of college: an education. Student-athletes are not employees, and their participation in college sports is voluntary. We stand for all student-athletes, not just those the unions want to professionalize.”

While consistency in public statements is important, they must too be credible in order to be effective. The NCAA, which reportedly makes about a billion dollars a year, is clearly about revenue, it is about money and it’s clear that it is fighting against, not for, student-athletes to protect the revenue streams.

Here’s where the NCAA runs into its credibility issues. The Association and the colleges drive revenue based upon the efforts of the athletes, yet are attempting to convince judges and lawmakers that compensating them would impinge the purity of the student-athlete and do “far more harm” than paying them.

The NCAA and its member colleges and universities generate millions of dollars each year by using current and former student-athletes’ images for everything from the sale of jerseys, video games, DVDs, photos – not to mention revenues from ticket sales and television contracts. The NCAA contends that the student-athletes compensation comes in the form of scholarships, education, housing and so forth. The problem is that this message does not affectively address the issue of fairness. Additionally, The fact that college athletic departments seem to be faced with a never-ending stream of scandals and cover-ups doesn’t help the NCAA position either.

As judges, lawmakers and others make important decisions about the fate of college athletics they will have to figure out whether or not the NCAA’s actions are lawful. However, the essential theme might in fact be “fairness.” When considering the myriad of challenges facing the NCAA, it’s apparent the NCAA and its member colleges are on the wrong side of the fairness question. Most Americans naturally support the idea of fairness (and free markets) and it’s likely the court of public opinion will too.

There is a lot of history on the topic and in most cases fairness has won in the courts and in Congress. Take for example the case of free agency in Major League Baseball. In 1879, what was then MLB adopted the reserve clause, which essentially gave team owners full control of which teams players played for and how they were compensated. That held until the early 1970s when St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood set in motion a challenge that eventually gave way to the modern free agency system. Following the 1969 season Flood objected to a trade to the Philadelphia Phillies. In a letter to commissioner Bowie Kuhn he wrote:

“After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

“It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.”

What was Flood asking for? He wanted fairness. The case eventually led to the United States Supreme Court in 1972, which in turn led to the nullification of the reserve clause. Since then every other major American team sport has succumbed to the law and fairness.

In the coming weeks a federal judge in Oakland, Ca will have to decide whether the NCAA’s business practices represent a violation of U.S. anti-trust laws in the O’Bannon case and whether the NCAA has acted fairly.